|

June 20, 2025

COME JULY 31 MILLIONS WILL KNOW THE NAME “FEDERAL CIRCUIT”

We live in an IP language bubble, where we use words unfamiliar to the world outside the bubble.

Federal Circuit—The court is known to possibly 100,000 people in IP and elsewhere, but unknown to most of the estimated 245 million U.S. English speakers. That’s about to change. On July 31 the Federal Circuit will hear arguments in V.O.S. Selections, Inc. v. Trump, which involves the president’s constitutional authority to impose tariffs. Major media will report on the case persistently. Suddenly millions will know of the Federal Circuit. From an IP language viewpoint, that will be good.

Comprising—The most common word in patent claims is an “open” term inside the IP bubble and a “closed” term outside. To get everyone on the same page, I advocate using “including” in patent claims.

Readers—Commenting on last week’s column on achieving excellence in IP/ legal documents, readers said wine only makes you think you’re achieving excellence.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

June 13, 2025

TIPS FOR ACHIEVING EXCELLENCE IN IP/LEGAL DOCUMENTS

Unless you’re a novelist, don’t write in a stream of consciousness style. IP and legal documents need organizing before the first draft.

- Know what you want to say. Think it through over a glass of wine. For longer documents, write and revise an outline.

- Organize in a logical sequence. To persuade, make your strongest arguments first and sometimes your weakest never.

- If the audience doesn’t know the subject, give background. Also, as Judge ROBERT BACHARACH says, “To understand how the analysis will unfold, the reader needs to know from the outset what the conclusion is.”

- After you’ve written a draft, edit and edit some more. Strive for clarity, conciseness, and plain English words.

- If you have collaborators or an editor, give them time for review—and a glass of wine. But never let them see an early draft.

- Like wine, let your document age before you declare it ready. It’s amazing what you can see with fresh eyes!

Suggestions are Invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

June 6, 2025

COMMENTS FROM THE READERS

Formal Logic Rules: A friendly reader commented, “This stuff does not play well in my linear mind.” Granted, logic rules aren’t silver bullets. You can make winning arguments without knowing logic rules if you support your conclusions with common-sense reasoning.

Federal Circuit v. CAFC: Why do people persist in using “CAFC”? One reader thinks it might be because the court’s internet address is cafc.uscourts.gov. Another reader, STEVE MURRAY, wonders whether CAFC is being used to reduce the word count in patent briefs.

Unneeded Parentheticals: BRYAN GARNER isn’t a reader, but he knows of this column. In a recent article he said many judges and lawyers write, “Petitioner Herman Grundy (hereinafter ‘Grundy’).” If there’s only one Grundy in a case, a parenthetical isn’t needed. After the first mention, just write “Grundy” and give your readers credit for having intelligence.

Suggestions are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

May 30, 2025

IP LANGUAGE ANNOYANCES

Readers send me words and phrases that irritate them. Here are three:

Register or Registrar: The head of the U.S. Copyright Office is the Register of Copyrights, not the Registrar. The Register’s title has been in the mainstream media since the issue of authority to fire her arose. Often the media get it wrong.

Log In or Login: The verb form “log in” is used when referring to the action of entering a system, while “login” as a noun refers to the credentials used for that action. Simple. You use your login to log in.

Federal Circuit or CAFC: The first chief judge insisted on “Federal Circuit” because he wanted the public to understand that the new court was at the same level as the better-known courts of appeals for the regional circuits. (After Wednesday’s tariff decision by the U.S. Court of International Trade, the Federal Circuit may have a higher profile. The Federal Circuit has exclusive jurisdiction over appeals from that court.)

Comments are Invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

May 23, 2025

WRAPPING UP: USE OF LOGIC TO CONSTRUCT REASONED ARGUMENTS

Good legal writers, including IP writers, often make their arguments using the science of logic. Last week we summarized deductive reasoning, expressed in syllogisms — a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion. If the premises in a proper syllogism are true, you can be certain that the conclusion is true.

Another main category of logic is inductive reasoning. Here, you can’t be certain that the conclusion is true. In inductive reasoning, a broad generalization is arrived at by observing many narrow instances. E.g., “A is smart, B is smart, and C is smart. Therefore, everyone is smart.” This is “the fallacy of hasty generalization.” Closely related is reasoning by analogy. Analogies are used to compare legal issues with precedents. Whether an analogy is strong or weak is a matter of judgment.

The language of logic is dense. For a plain English discussion, see Logic for Law Students, 69 Univ. of Pittsburgh L. Rev.1(2007). Next week: back to ordinary IP language. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

May 16, 2025

MORE ON LOGIC: CONSTRUCTING LEGAL ARGUMENTS

Last week I covered the logical fallacy called “begging the question.” Today I will touch on syllogisms.

A syllogism is an argument in which a conclusion is inferred from two premises. An example of a valid syllogism: (1) “All people are mortal” (major premise); (2) “Socrates is a person” (minor premise); and (3) “Therefore, Socrates is mortal” (conclusion). An invalid syllogism: “All lawyers are runners. Smith is a lawyer. Therefore, Smith is a runner.” The major premise is false because not all lawyers are runners.

Instinctively or consciously, the best writers often structure their arguments in syllogistic form. They think in syllogisms too. That’s called, “thinking like a lawyer.” Fashioning premises based on known facts pertinent to your case can be a lot of work, but explicit reasoning keeps people from making arguments based on mere undisciplined hunches.

Syllogisms are explained in detail in Logic for Lawyers: A Guide to Clear Legal Thinking, (3d. ed. 2001, $30 on Amazon). Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

May 9, 2025

WHAT’S THE MEANING OF “BEGS THE QUESTION”?

Today this phrase is used in two ways.

Ever since Aristotle, it’s been used to describe a logical fallacy. “Begging the question” is an attempt to prove a claim with a premise that restates or presupposes the claim. “Opium induces sleep because it has a soporific quality.” This statement uses a synonym to support the conclusion already stated. If such an argument takes multiple steps, it may be called “circular reasoning.” Lawyers know the concept.

But English is a living language. According to The Washington Post and Bryan Garner, lots of people now use “begs the question” to pose a follow-up question. They write that something “begs the question” and then state the question. A recent article said Post editors disapprove. “If you mean that something raises the question, write that it raises the question.” Bryan Garner, however, says the newer usage of “begs the question” has become widespread and he accepts it.

Be aware of the two usages. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

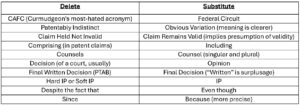

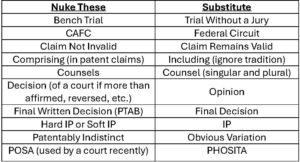

LIST OF EDITS INCLUDING READER SUGGESTIONS

|

Many of these were explained in past columns. Comments invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

April 25, 2025

ARE EM DASHES A SIGN OF WRITING PRODUCED BY AI?

This question is being debated on social media—emotionally—by professors, journalists, and other word nerds. Last week it was covered by The Washington Post.

An em dash is a punctuation mark that’s longer than a hyphen—as wide as a capital M. It’s an alternative to commas, parentheses, and colons—for adding emphasis or flair or causing the reader to pause.

Some writers are convinced that generative AI tools such as ChatGPT favor em dashes, which might cause editors to suspect that human writing with em dashes is AI-generated. Others haven’t seen a problem. A representative of OpenAI told the Post, “it’s possible,” but the firm is continuing to improve ChatGPT’s writing ability.

The Curmudgeon’s take: Em dashes are still standard, educated English and appropriate for IP documents such as briefs and memos. To avoid clutter, use em dashes sparingly—and no more than two in one sentence.

Comments are welcome. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

April 11, 2025

A BETTER NAME FOR PTAB OPINIONS THAT ARE DESIGNATED “INFORMATIVE”

The USPTO highlights notable opinions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board by designating them “Precedential” or “Informative.” Recently the Office drew attention to an opinion in Cambridge Mobile Telematics that apparently was the first designated Informative in a while.

The Office defines Informative as, “providing Board norms on recurring issues, guidance on issues of first impression to the Board, guidance on Board rules and practices . . . .” Does this mean an opinion can be uninformative? Of course not. Every opinion is informative, at least to the parties.

How about changing “Informative” to “Very Informative”? The word “very” can be meaningless, but in this context it would act as a strengthener. The effect would be to make clearer that every opinion is considered informative.

BTW, when opinions are de-designated, it probably makes the authors a little sad. Comments are welcome. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address. Click here for the Curmudgeon Archives.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

April 4, 2025

POINTERS ON DRAFTING LEGISLATION

You may be asked to advise on IP legislation. With the new U.S. Congress underway (119th Congress, 2025 and 2026), it’s a good time for a refresher on legislative writing and editing.

Basic Principles – The goals are the same as for other legal writing: clarity, conciseness, and good organization. The quote attributed to many people, “Sausage and legislation are better not seen in the making,” refers to political dealmaking. Recommended attire for drafters is body armor.

Avoid Unnecessary Detail – The U.S. patent and copyright statutes have become word swamps that may be contributing to litigation. Leave details to regulations when possible.

Curmudgeon’s Pet Peeves – (1) For clarity, bills to amend patent law section 101 should refer to “subject matter eligibility,” not just “eligibility.” (2) Definitions may be needed in bills, but they should come at the end. The chapter in the patent code on patentability starts with section 100, “Definitions.” Poor organization.

References – Garner, Guidelines for Drafting and Editing Legislation (2016); Strokoff and Filson, Legislative Drafter’s Desk Reference (2024).

Comments are welcome. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

March 28, 2025

READER SAYS “OH, COMMA ON!”

Comma Clutter – Last week I asserted that many IP briefs and opinions are cluttered with unneeded commas. I said don’t put a comma everywhere you would pause if reading aloud.

Friendly readers questioned this. ROBERT SACHS relishes the comma. He said, “Oh, Comma on!” (He’s a budding comedian). JEFF GLUCK wondered whether The Curmudgeon is moving toward sloppiness. He believes commas are meant to harmonize speaking and writing, among other purposes.

Not to Worry – Fewer commas are used now, but no one is ignoring them in formal legal or technical writing. Garner’s Modern English Usage (2022) discusses 10 uses for commas. They’re disappearing, though, after short opening phrases and before “and” and “or” in compound sentences. Briefs written for the U.S. Supreme Court show the lighter use of commas in long legal documents, but clarity still rules.

Commas Can Be Protected — The Apostrophe Protection Society was founded in 2001. It has 4,500 members in the UK and the US. Membership is free.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address. Click here for the Curmudgeon Archives.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

March 21, 2025

KEEPING UP WITH TODAY’S ENGLISH IN THE U.S.

Avoid Comma Clutter – Many IP briefs and opinions are cluttered with commas that are considered unnecessary today. The rule of thumb to insert a comma everywhere you might pause if reading aloud is obsolete. Examples, with unnecessary commas in brackets:

“She’d prefer ice cream [,] and he’d prefer peaches.” “By half past noon [,] the clock was broken.” “He was unprepared [,] too.” (Rebel with a Clause, Ellen Jovin).

To ensure clarity, however, most experts still use the “Oxford comma” to separate the last item from the next-to-last in a series. E.g., “The Joneses, The Smiths, and the Nelsons.” (Bryan Garner).

“Whom” Seems to be Fading Away – The full list of old grammar rules on “who” v. “whom” is too hard to remember. I trust my ear and use “who” unless it sounds weird. There are instances when “whom” is needed. E.g., “For Whom the Bell Tolls” (Ernest Hemingway and Metallica). If it doesn’t sound right, recast your sentence. “In 200 years, ‘whom’ will be extinct.” (Edward Sapir).

I welcome your suggestions. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

March 14, 2025

COPYRIGHT LAW: CREATING THE SAME WORK INDEPENDENTLY

Last week I discussed “exclusive right” and “right to exclude others” as used in U.S. patent law. How about copyright law?

A copyright isn’t an “exclusive” right as the word is defined in dictionaries. Exclusive means limited to only a person or group of persons. Copyright law doesn’t have the concept of novelty. Two parties who create the same work independently both have a copyright. Independent creation rarely arises in practice, but copyright experts explain it to illustrate one of the ways copyrights differ from patents.

The legendary Secondary Circuit Judge Learned Hand put it this way in 1936:

“[I]f by some magic a person who had never known it were to compose anew Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, they would be an ‘author,’ and if they copyrighted it, others might not copy that poem, although they might of course copy Keats.”

I recommend that careful writers avoid calling copyrights exclusive. I welcome your suggestions for future columns. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

March 7, 2025

CAREFUL WRITING: IS IT AN EXCLUSIVE RIGHT OR A RIGHT TO EXCLUDE?

Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution provides that Congress shall have the power to secure to inventors for limited times “the exclusive right” to their inventions. Under the patent statute, however, a patent grant is defined as a “right to exclude.”

The “right to exclude” is interpreted more narrowly than “exclusive right.” For example, an inventor may obtain a patent on an improvement to a patented invention with broad claims that is owned by someone else. The improvement inventor can’t practice its invention without obtaining a license under the broader patent, sometimes called a “blocking patent.” So, the right to exclude is not an unqualified exclusive right.

Because Article I, Section 8 doesn’t require Congress to exercise the full scope of the power given to it, the statutory definition of a patent isn’t in conflict with the constitutional language. Refer to patents as “rights to exclude.”

I welcome comments. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

February 28, 2025

THE D-WORD AND OTHER TRENDS

Deep — When the Chinese company DeepSeek burst on to the AI scene last month, people began noticing that “deep” is the trendiest of words. A search this week revealed 731 startup companies with “deep” in their names. To ordinary people, the “D-word” seems to mean something like “cutting-edge tech,” although to AI experts it apparently means “deep neural networks.”

Big Tech Bros — Remember when “technology” simply meant “applied science” or “engineering science”? It gradually was supplanted by “tech” and then by “big tech.” The hot issue now is, “Who are the big tech bros?” English is a living language.

Comprising — Last week I suggested “including” for patent claims instead of “comprising.” Comprising has a meaning to lay people exactly opposite to the meaning given to it by courts in patent claims. See Black’s Law Dictionary. Reader WALT LINDER said he in fact uses “including.” I hope Walt’s a trend setter.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

February 21, 2025

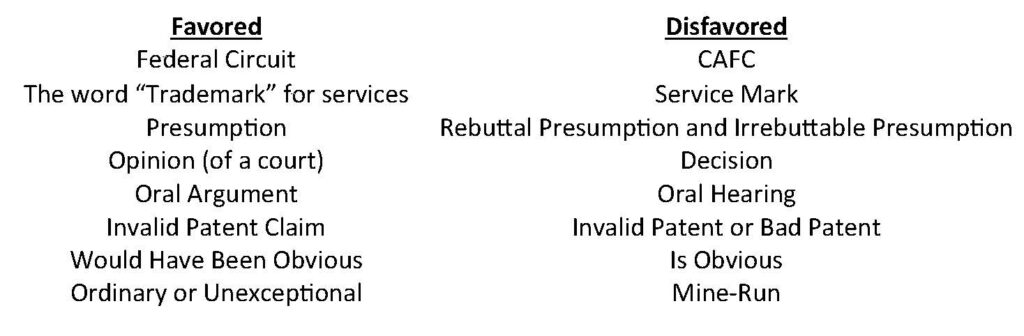

CURMUDGEON’S WORDS AND PHRASES (UPDATED)

|

Most have been explained in past columns. Comments invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

February 14, 2025

CIVILITY IN IP (PART 1)

Defining It – Civility is a core principle in every workplace. For purposes of IP, it means being respectful and courteous when interacting with co-workers, adverse parties, courts, and agencies, among others — in writing and orally. Civility helps ensure that everyone can be heard.

It’s Declining — While judges have commented that IP attorneys often are more respectful and courteous than other attorneys, experts say civility in society overall has been declining for years, or even decades. In a 2023 ABA survey, 85 percent of 1,000 people who responded believed incivility was more common than 10 years earlier.

Incivility — Bad behavior includes rude emails, unnecessarily aggressive court filings, sarcasm, condescending comments, and inappropriate interruptions. Some may consider the notion of civility quaint, but it has real-life costs including wasteful litigation and loss of employees and clients.

Instilling It — Consider more programs in law schools, mentoring employees, more meetings between parties before deciding to sue, and alternative dispute resolution. Stay tuned.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

February 7, 2025

PEACEKEEPING: AVOID SAYING “HARD IP” OR “SOFT IP”

I hear these terms occasionally. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, “hard IP” is “intellectual property such as a patent . . . .” “Soft IP” is “intellectual property such as a copyright . . . .” The first known usages were in the 1990s.

Sources other than Black’s provide a variety of definitions. Some include trademarks and trade secrets in soft IP. In the context of semiconductor design, “soft IP” seems to refer to flexible, customizable designs and “hard IP” refers to less flexible designs.

One author says the terms hard IP and soft IP are “controversial” among patent and copyright practitioners. Another complains that soft IP “implies that patent law alone is hard.” One of my friends argues that copyright law in fact is much harder than patent law.

The Curmudgeon’s advice: Don’t use “hard” and “soft.” We don’t need fights for no reason.

Your suggestions for future topics are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

January 31, 2025

READERS COMMENT ON “INVENTION” AND “CAFC”

Invention — Reacting to last week’s column on the words “invention” and “innovation,” reader ROBERT SACHS says he was taught that you never use the term “invention” or “present invention” in a patent specification. The only things that are “inventions” . . . are those that are claimed. Everything else is simply a description . . . .”

He says courts have limited the scope of claims because the drafter characterized the “present invention” in the body of the specification. Also, he never uses “innovation” in a patent because there’s no need for it.

CAFC — A reader commented on the January 17column, which noted that the Federal Circuit’s first chief judge didn’t like “CAFC.” The reader doesn’t like it either, but she believes the web address for the court, cafc.uscourts.gov, may be an obstacle to getting rid of it.

Suggestions Are Welcome. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

January 24, 2025

USING “INVENTION” AND “INNOVATION”

The U.S. patent code says “invention” means “invention or discovery.” That may be the world’s least helpful definition. Merriam-Webster defines “invention” as “a product of the imagination.” Some people think an “invention” must involve an idea that is new.

What’s the distinction between “invention” and “innovation”? The University of Pittsburgh has a 5-minute video on this question as it relates to technology. WIPO says innovation means “doing something new that improves a product, process or service.” In U.S. parlance, however, innovation has taken on a much broader meaning. It can be almost any activity in life that implies improvement or progress.

To be as clear as possible when you use the word “innovation,” I suggest specifying the type of innovation, such as “technological innovation,” “business innovation,” or “social innovation.” In some contexts, you might say “creation,” which is less over-used.

Do you have thoughts? Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address. Click here for the Curmudgeon Archives.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

January 17, 2025

READERS HAVE COMMENTS

The Applicant States — Last month one reader said it seemed odd to start a sentence in a patent document with “Applicant states.” He uses “The Applicant states.”

According to another reader, ROBERT SACHS, the rule is to use “the” if a referent is sufficiently known. Robert, however, seems to prefer just “Applicant states.” He says he’s old school.

Jones Italicized? — An anonymous reader says that when a patent is cited by referring to the inventor’s name (e.g., “Jones teaches. . .”), the name should be italicized. Yes, titles of cited documents usually are italicized, but it might be a heavy lift to get writers to do it in patent citations.

Language Changes Take Time — When the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit was established in 1982, the legendary Chief Judge HOWARD MARKEY urged the short form “Federal Circuit,” not “CAFC.” He felt that “Federal Circuit” accorded more status. Still today, the struggle continues between status supporters and acronym addicts.

Suggestions are welcome. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

January 10, 2025

DO WORDS MATTER?

To wrap up 2024, let’s look at the state of language outside of IP. Politico reports that Senator BRIAN SCHATZ from Hawaii, a Democrat, knows why Democrats lost the election. “They didn’t talk like normal people.”

Schatz recalls Harris saying, “I’m going to center the needs of the working class.” Shatz doesn’t know “anyone else in the world” who uses “center” that way. And Democrats were fond of the expression “making space for.”

He says Trump “speaks like people speak now, including profanity. It’s normalized. . . . And you know what, everybody says it in this country with very few exceptions.” Trump is “the guy at the end of the bar. For better or worse.”

Schatz may be joking, but while profanity is humor for comedians, it’s a way for other people including politicians of both parties to express annoyance, disdain, and hate. Is there a link with the shocking decline of public confidence in courts to 35 percent (Gallup)? Let’s keep profanity out of IP.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

December 20, 2024

“APPLICANT” OR “THE APPLICANT”?

Reader WALT LINDER wonders whether it’s proper to start a sentence in an IP document with, “Applicant states . . . .” He says it sounds odd to him, so he inserts “The” before “Applicant.”

Walt, you’re not the only one who thinks it’s odd to omit the definite article “The” before names like “Applicant” or “Petitioner.” This seems to be a peculiarity of U.S. patent prosecution practice. A good general rule is to write like educated people talk. You’d say, “The dog is barking.”

Here’s another naming tip. In inter partes cases, refer to the parties in the style of the Supreme Court and the Federal Circuit. The courts use the real names of the parties (e.g., Smith and Jones) all through their opinions. Names of people (and companies) help the reader remember the parties and make it easier to follow the story. The USPTO’s PTAB uses “petitioner” and “patent owner,” which some say makes for harder reading.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Happy Holidays!

The Curmudgeon

December 13, 2024

BE PRECISE WITH “NAMELY” IN TRADEMARK IDENTIFICATIONS OF GOODS

The word “namely” has appeared in the identifications of goods and services in millions of U.S. trademark applications and registrations. It could be as common as “comprising” in patent claims.

This year the USPTO’s trademark board encountered an issue with “namely” in the identification of goods for the mark SAFELOCK. The identification read, “Components for air conditioning and cooling systems, namely, evaporation coolers.” (Emphasis added).

The mark had been used in commerce with components, but had not been used in commerce with evaporation coolers. The trademark board said in a precedential opinion that the words following “namely” are always interpreted more narrowly than the words that come before “namely.” The registration was cancelled. In re Locus Link USA.

The Curmudgeon offers no opinion on whether the case was correctly decided but recommends precision in identifications of goods and services. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

December 6, 2024

PRONOUNCING “CONDITION PRECEDENT”

The Rule – “Condition precedent” is a term in contract law. It’s used often in IP agreements. How do we pronounce “precedent” in “condition precedent”?

“Pre-seed-ent,” not “press-e-dent,” is preferred.

Explaining It – As an adjective, “precedent” means preceding in time or order. A condition precedent is an act or event that must occur before a duty to perform something arises. It precedes. Conversely, a “condition subsequent” brings something to an end.

Contrast this with the noun “precedent,” which is something that serves as an example or rule to authorize or justify a subsequent act of the same or an analogous kind. The noun is pronounced “press-e-dent.”

Ranting About It – Lawyers have been taught this distinction in pronunciation for 200 years, but lately the Curmudgeon has noticed that increasing numbers haven’t learned yet. A condition precedent precedes. How hard is that?

Comments are always welcome. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

November 22, 2024

LINGO TO KNOW FOR DISCUSSING CHANCES OF IP BILLS IN CONGRESS

Lame Duck – In politics a lame duck is an elected official whose successor already has been elected. The current U.S. Congress with many lame ducks will end before Jan. 3, 2025, when the new Congress starts. Lame ducks have limited power and influence. They may be inclined to put bills off, or they may be inclined toward action because they don’t fear consequences.

Kicking the Can Down the Road – Politicians began using this expression in the 1980s. Its name comes from the children’s game “kick the can.” It describes the practice of delaying an issue in hopes that someone will make a decision later. Soon we will know whether the lame duck Congress will kick IP bills down the road this year.

250 Columns – Today’s column is the 250th, counting columns written since they resumed in 2022 and older ones. I’m grateful for your suggestions.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

November 15, 2024

IS A PATENT “IP” OR IS IT AN “IP RIGHT”? (CONT.)

This was the question last week. I appreciate the comments submitted by readers. I’ll try to distill them.

Property — tangible or intangible — is a “bundle of rights.” The rights bundle for inventions is similar to the rights bundle for land. For patents, the rights bundle is defined by the constitution, statutes, and court decisions. Key rights include the right to exclude, the right to possess, and the right to transfer.

Remember what Ralph Waldo Emerson said: “. . . foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Usage of the term “IP” is not always consistent. Inventions that aren’t protectable and therefore not property are often called “IP” anyway. If you’re discussing patent-eligible inventions, however, you’re discussing property rights. For clarity, let’s call a patent an “IP right.”

Next week I’ll find something easier. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

November 8, 2024

ARE PATENTS “INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY” OR “INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS”?

When I searched online for the meaning of “IP,” the first answer I got was “Internet Protocol.” Darn it!

Anyway, how should we use the terms IP and intellectual property in our field? Black’s Law Dictionary gives two definitions of intellectual property (quotations simplified):

- A category of intangible rights, such as patents, protecting commercially valuable products of the human intellect.

- A commercially valuable product of the human intellect, in a concrete or abstract form, such as a patentable invention.

With the first definition, your patent is IP. With the second definition, it’s your invention that’s IP, making your patent an IP “right.” Which definition do you use? Which is the more common usage? Does it matter? (Let’s leave trademarks and copyrights for another time).

BTW, in 1972 IPO apparently became the first association to use the term “intellectual property” in its name. Soon other associations followed suit. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

November 1, 2024

DISH OF THE SEASON: “WORD SALAD”

We’ve heard the term word salad a lot lately. Word salad has no calories. It’s a difficult-or-impossible-to-understand mixture of confused words or phrases.

The first known use of the term word salad was in 1904. According to Merriam-Webster, in early years it described “the disordered speech of the mentally ill — but now it’s also being used to describe political speeches.”

Common word salad, I’ll call it, often happens when a speaker doesn’t know the answers to questions. Word salad virtuosos, on the other hand, know the answers, but they choose to speak confidently with many words and say nothing.

Word salad isn’t limited to politics. In the Nexstep opinion reported in the IPO Daily News last week, the Federal Circuit upheld a district court judge who rejected expert testimony that he characterized as word salad. The Federal Circuit used the term too.

Send your suggestions for future topics. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

October 24, 2024

CAMPAIGNING FOR LITERACY: THE WORD MUSEUM

Readers with a spare hour in downtown Washington, DC should visit PLANET WORD MUSEUM, the $60 million brainchild of philanthropist ANN B. FRIEDMAN. Friedman believes literacy trends are moving in the wrong direction. The number of adults in the U.S. who can’t read is 32 million.

The six state-of-the-art galleries are directed not to IP or STEM words, but to words generally. A featured exhibit is a 22-foot-high, 50-foot-wide interactive wall, “Where Do Words Come From?” Many believe that our otherwise highly literate IP and STEM professionals need to understand better how to translate the discourses used in their arts to the discourses used in the language arts.

The museum occupies the Franklin School, a Washington landmark built in 1869 and renovated top-to-bottom before the 2020 opening. It was from the Franklin School roof in 1880 that ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL made the first wireless voice transmission to his nearby laboratory at 1325 L Street. He called it his greatest invention.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

October 18, 2024

WRITING INTERNAL MEMOS; REORGANIZING PTAB OPINIONS (CONT.)

Demise of the Legal Research Memo? — Traditionally, formal memos are prepared to analyze the law and facts relating to a client’s situation. They may be called research memos or assessment memos. They’re used within a law firm or company and written before arguments are presented to a tribunal or adversary.

Recently BRYAN GARNER said, “Some lawyers don’t write memos anymore, and that’s a bad idea.” With the rise of emails, lawyers claim simple “yes” and “no” answers save time and money. If you have a culture requiring research to be reduced to writing in a form that allows everyone on the team to understand scope of research, answers, and context, Garner insists that you’ll get superior decision-making.

More on PTAB Opinions — Last week I mentioned the suggestion that the PTAB should consider changing how its opinions are organized. No one has offered any solutions yet. We’ll come back to this. BTW, could the PTAB eliminate those tedious paper numbers that clutter final written decisions?

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

October 11, 2024

READING AND WRITING IP OPINIONS AND MEMOS

Most judges and lawyers are excellent writers, but The Curmudgeon has improvement ideas.

U.S. Supreme Court – The court’s syllabuses are a complete waste of time. They aren’t part of the court opinion. They’re written by the Reporter of Decisions and they’re way too long to serve as summaries. Go directly to what the justices say.

Federal Circuit – The court’s opinions are generally well organized. Perhaps explanations of the technology could be made a little easier. It’s a challenge in complex technologies.

PTAB –JUDGE DYK has suggested that PTAB opinions are hard to read and the PTAB should consider changing how the opinions are organized. Do our readers know how to do it? For starters, could the PTAB use the names of the parties in its opinions, as courts do, not “petitioner” and “patent owner”?

In-House Memos – Next week.

Comments are always welcome. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

October 4, 2024

FOOTNOTES, CONTINUED FROM LAST WEEK

An anonymous reader comments, “. . . my law school writing teacher said the footnotes are where the important facts and issues reside. Be sure to read them.” But many people resist reading footnotes and that’s not likely to change.

Last week I said “no” to substantive arguments in footnotes, but I’ve now realized that the U.S. Supreme Court is writing substantive footnotes. Majority opinions comment on dissenting opinions in often-lengthy, small-type footnotes, and dissenting opinions comment on majority opinions the same way. Reading glasses needed. Are the justices trying to send messages to their colleagues?

When Bryan Garner advocated that citations to court cases should be moved to footnotes, he was speaking about legal memos, briefs, and court opinions. Law reviews already use footnotes for case citations. The dreaded Bluebook suggests it

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

September 27, 2024

USE FOOTNOTES SPARINGLY IN IP WRITING

A reader suggested that the Curmudgeon address footnotes in IP and legal writing. A debate over footnotes goes back to at least 2008, when BRYAN GARNER and the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice ANTONIN SCALIA co-authored a book titled Making Your Case.

An issue was whether legal citations should be in the main text or in footnotes. Scalia stuck with the conventional way, for briefs and court opinions, which is to put the citations in the text. Garner wanted to move citations down to footnotes. MY ADVICE: Keep citations in the text, but at the ends of sentences, where they will be less distracting.

A continuing issue is whether sentences or paragraphs containing less-important substantive arguments should be in footnotes. MY VIEW: Don’t put an argument in a footnote if you want it read.

BTW, Scalia once said, jokingly, “There is one field of law where they don’t write in either English or Latin. That field is patent law.” Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

September 20, 2024

WARNING LIGHT FOR LEGALESE: WORDS ENDING IN “ION”

A word ending in “ion” can be a noun created from a verb. Use the verb form to avoid wordy sentences.

|

Called “zombie nouns,” these nouns are common in legal and academic writing. A verb is an action word and doesn’t require extra words. Too many zombie nouns can make your work difficult to understand.

Sometimes you will want to use an “ion” word to emphasize an important idea. E.g., you may want to write “litigation” instead of “litigate” or “competition” instead of “compete.” And you may want to use the noun form so it can be the first word in a sentence. But if you can edit out a word that ends in “ion,” do it.

I invite your suggestions for future topics. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

September 13. 2024

SELECTING THE RIGHT WORD INSTEAD OF THE ALMOST RIGHT WORD

We often discuss the “right” IP specialty words. Good IP writing, though, also requires knowing the “right” connectors and other common words that educated people use throughout all English writing.

Judge BOB BACHARACH says, “Choosing the right preposition [or other short word or phrase] may require memorization or consulting a list.” Here are a few examples of words that are right and not quite right.

Recent Edits Made in IPO Newsletters

Changed “at the minimum” to “at a minimum.”

Changed “assisting in” to “assisting with.”

Depends on the Usage

Judge Bacharach says to use “compare with” if comparing the similarities and differences of things; use “compare to” if likening things to one another. Some might say it’s a distinction that’s too fine.

Can Be Either

In the U.S., both “different from” and “different than” are acceptable. In the UK, you can say “different to.”

Do you have pet peeves about words that aren’t quite right? Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

September 6, 2024

ENGLISH CLASS REFRESHER: KEEP SUBJECT, VERB, AND OBJECT CLOSE TOGETHER

Let’s review this rule today:

“Keep the essential parts of a sentence– subject, verb and object — close together. And keep the essential parts toward the beginning of the sentence.”

“Legalese” may result when writers insert clauses, phrases, or modifiers between the essential parts, making the sentence harder to understand. Click here for an example. The reason for putting the subject, verb, and object near the beginning, experts say, is that readers approach each sentence by looking near the beginning for “the action.”

Some M.I.T. researchers have been studying legalese. They believe legal writers, more than others, use “center-embedded clauses” to add details after the first draft. The M.I.T. folks also have a debatable theory that legalese is used to create a “magic spell.”

We should try to remember the rules from English class, but the first rule always is to keep your language clear and concise. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

August 30, 2024

IS THE U.S. GOVERNMENT GUILTY OF WORD INFLATION?

An ABA newsletter reports that “Supreme Court Justices are Writing More Concurring Opinions to Accompany Rulings.” In the just-completed term, the average number of concurring votes per majority opinion was 1.44. The number for the period from 1946 to 2023 was 0.80. (Every justice who joined in a concurring opinion was counted as a vote.)

Professor MEG PENSROSE published an article last year titled “Legal Clutter: How Concurring Opinions Create Unnecessary Confusion and Encourage Litigation.” The Curmudgeon sides with the professor.

IP regulations now may be more verbose. The question is not whether regulations are needed, but whether the regulations adopted are wordy. The Office of the Federal Register’s 2023 edition of CFR Title 37 had 1,074 pages, up from 916 in 2019.

Similarly, IP legislation in the modern era covers microscopic issues that many say are better left for agencies and courts, if they ever arise. The landmark Patent Act of 1952 was short and generally clear. Compare the 2011 AIA.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

August 23, 2024

WANT TO START A TREND OF USING “INCLUDING” IN PATENT CLAIMS?

Reader RAY DOSS asked why, in last week’s preferred list of IP words and phrases, the word “including” was listed as preferred over “comprising.”

“Comprising” is the most common word in patent claims. It’s used in the transition between the preamble and the body of the claim. In patent parlance, “comprising” means including but not including exclusively. The word makes a claim open-ended. Every patent attorney knows this.

The problem is that about 330 million people in the U.S. who aren’t patent attorneys don’t know the specialized patent law meaning for comprising. To them, comprising means “consisting of exclusively; embracing to the exclusion of others.” See Black’s Law Dictionary.

The Curmudgeon thinks “including” would be a better word for patent claims. Has anyone actually used “including”? If you want to be the first, you could start a healthy trend.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

August 16, 2024

CURMUDGEON’S LIST OF PREFERRED WORDS AND PHRASES

|

Updated August 14.

Comments and questions are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

August 9, 2024

IP WRITERS MUST BE EXPERT EXPLAINERS

BRYAN GARNER, who is often quoted in this column, says, “. . . lawyers above all must be good explainers.” That’s even more true for writers in the IP field. IP writers must explain inventions and creative works that are new to the world.

Judge ROBERT BACHARACH emphasizes that your opening words should explain the context for what follows. Help the reader get into it. Explaining the context up front was Bacharach’s first topic during a recent writing webinar sponsored by the DC Bar.

A little more on explaining:

- In IP, we’re writing for intelligent, highly educated people. Explain just enough for understanding, but don’t burden people with unnecessary details.

- Present your information in manageable chunks.

- If writing to persuade, ordinarily start with your strongest arguments.

- If you constantly practice writing clearly and concisely, it will become second nature to you.

- Everyone needs a ruthless editor.

Send me your suggestions. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

August 2, 2024

WRITING IP SHORT

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in 1863 arguably is the greatest short piece of writing in American history –269 words in the standard version.

Lincoln was the only U.S. President to hold a patent, but less well known is that he was a sought-after, travelling litigator for about 24 years who appeared in more than 300 cases in federal courts including some two dozen patent cases. Litigation experience might have taught him the benefits of brevity.

Almost every first draft IP document needs shortening. Descriptions of inventions in patent applications are among the few IP documents where longer may be better. IP writing can be shortened in the same ways as other writing.

You should prune the large limbs first – e.g., consider scrapping entire lines of argument. Then prune the small limbs. Use short words and phrases. “About,” not “approximately.” “Under,” not “pursuant to.” Omit needless words and phrases like “The fact that.” Excise redundancies like “past experience” or “general public.”

I’ve reached my word limit for this week. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address. Click here for the Curmudgeon Archives.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

July 26, 2024

USING ORDINARY LANGUAGE

Ejusdem Generis — Do you know this phrase? Prof. DENNIS CROUCH reports that it is used in the Feliciano case involving military pay, one of only two Federal Circuit cases the U.S. Supreme Court has accepted so far for the October 2024 term.

If you don’t know, Ejusdem Generis is a 17th century Latinism that means “of the same kind.” It is used as the name for the rule that when a general word follows a list of specifics, the general word will be interpreted to include only items of the same class as the specifics. Do we need a Latin name for this? Just state the rule. Use Latin sparingly!

Not Obvious or Nonobvious? — In a Federal Circuit opinion on Monday, Judge DYK, who knows his English, wrote “was not obvious.” No matter that the heading of Patent Act section 103 says “non-obvious,” often written without the hyphen. Saying “it was nonobvious” is like saying “it was nonhot today,” instead of “not hot today.” “Not obvious” is plain English.

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

July 19, 2024

MORE ON ACRONYMS

Turning the Tables — After last week’s column, a reader explained that she rebels when people use unnecessary acronyms like PHOSITA. She starts her response by writing the acronym. She then writes what the acronym stands for – e.g., “person having ordinary skill in the art.” Call it the long form. She uses the long form alone in the rest of her document.

Does she use too many words? Clarity is paramount. Remember, if an acronym isn’t intuitive, the reader may have to go back to recheck the definition. Readers want to go forward.

“NIL” Everywhere — Last week the Curmudgeon noted that the USPTO is holding a public roundtable on “NIL” (name, image and likeness). The NIL acronym is everywhere in college sports, but according to The Washington Post, “no one is sure exactly what it means.” The IPO Annual Meeting in Chicago will have a session on Sports Implications of IP. Attend and learn about NIL.

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address. Click here for the Curmudgeon Archives.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

July 12, 2024

CATEGORY 5 ACRONYM STORM FLOODS WASHINGTON

Although the U.S. Supreme Court may have killed the “deep state,” said to be the birthplace of acronyms, with its recent decision on Chevron deference, acronyms are alive and well.

The USPTO’s rule proposal on double patenting and terminal disclaimers (for nerds, the NPRM) had produced 351 public comments by mid-week. The comments collectively used thousands of acronyms such as TD (for terminal disclaimer, not touchdown) and OTDP (for obvious-type double patenting). IPO’s comment, for which The Curmudgeon can take no credit, was relatively acronym-free.

Also, IPO scored high on the easy-to-read scale by relegating most legal citations to footnotes. Bryan Garner says don’t clutter your text with citations and don’t put text in footnotes if you want it read.

And then there’s NIL. On July 1 the USPTO announced a public roundtable on “Protecting NIL, Persona, and Reputation . . . .” The Curmudgeon thought NIL was an acronym for name, image and likeness used in college sports and nil meant nothing at all. We’ll figure it out.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

June 28, 2024

IP LANGUAGE IN THE SUMMERTIME

USPTO as Lexicographer? –Reader JON PUTNAM wonders whether the USPTO could standardize claim language, reducing the need to guess at what the drafter meant. The USPTO’s common definitions could be modified by the applicant, but if they were, the modifications would have to be made explicit relative to the baseline. Thoughts on this?

Brief Brief – Last week IPO filed an amicus brief at the U.S. Supreme Court in Cellect v. Vidal that came in at 1,847 words, fewer than one-third of the 6,000 words allowed. IPO has a tradition of filing briefs that are not longer than necessary. For the brief, click here.

“Invention” Now a Hate Word? – On Monday Prof. DENNIS CROUCH, tongue-in-cheek, wrote that the U.S. Supreme Court is using “invention” in non-patent opinions as a hate word. To Justice Thomas, according to Crouch, “judicial invention” is a synonym for judicial activism. Justice Gorsuch recently condemned an opinion that “invent[ed]” a new doctrine. And on the liberal side, Justice Jackson wrote that the court “invents” new arguments.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

June 21, 2024

ACTING AS YOUR OWN LEXICOGRAPHER; USING DICTIONARIES

Self-Lexicographers — The rule that drafters can act as their own lexicographer is not unique to patent law. According to BRYAN GARNER, the idea appeared in American law as early as 1811in a case involving a will.

But don’t rush to be your own lexicographer. Garner urges using known words that are to be understood in their ordinary meaning if possible. Your definition may unclear or inconsistent, or a court simply may not accept it. Former Federal Circuit Judge RANDALL RADER In a 2005 dissenting opinion referred to “the often-cited but rarely followed lexicographer rule.”

Online Dictionaries — Print dictionaries have nearly disappeared. Professional lexicographers write for online dictionaries. Enter an internet search for the meaning of your word and you will get a choice of dictionaries. If in doubt, check multiple sources. One writer believes print dictionaries improve your spelling skills. Better keep one on your bookshelf just in case!

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address. \

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

June 14, 2024

JUSTICE GORSUCH RECOGNIZED FOR LEGAL WRITING

The Award — On May 27 the non-partisan Burton Foundation gave its annual award for distinguished writers and leaders in law to Supreme Court Justice NEIL GORSUCH. A program at the Library of Congress was hosted by CHRIS WALLACE, who called Gorsuch one of the “livelier, interesting” writers on the court.

Confront Other Side’s Arguments — As reported by Law360, Gorsuch said he first persuades himself that he has come to the right conclusion and his writing style flows from there. “. . . [cover] only one idea per paragraph,” the justice said. “And . . . proceed methodically and syllogistically, as best you can, to your conclusion, and candidly confront the strongest arguments on the other side.”

A Bit of His Style – Former IPO member and writing trainer ED GOOD analyzed earlier Gorsuch opinions from the 10th Circuit:

- Gorsuch averaged 25 words per sentence, short for a court opinion;

- He employed sentence fragments and sentences starting with conjunctions; and

- He used contractions (sparingly).

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

June 7, 2024

FIXING SMALL THINGS IN IP LAW IS HARD, BUT DON’T DESPAIR

A true story. The drafters of the 1952 patent act forgot to add letters for convenience to the paragraphs of section 112. The legendary Judge GILES SUTHERLAND RICH, one of the two key advisers to Congress on the 1952 act, gently suggested at every opportunity for decades that Congress should fix the oversight. It was never a priority. Finally, in 2011, it was done.

More things we could fix.

- Replace “patentably indistinct” in double patenting rules and directives with the easier-to-understand synonym “obvious variation.” (See my May 17 column.)

- Correct the error Congress made in codifying restriction practice in the 1952 act, by changing “independent and distinct” to “independent or distinct,” bringing the wording of the statute into line with accepted law.

- Clarify the case law, prospectively, that holds the indefinite article “a” in a patent claim means “one or more,” except when it doesn’t. (See my April 19 column.)

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

May 31, 2024

MORE IP WRITING AND SPEAKING TIDBITS

Keeping it short (cont.) – I reported last week that judges at the recent Federal Circuit Judicial Conference asked for shorter arguments and briefs. Here are some of their comments:

- JUDGE DYK suggested the USPTO should consider changing how PTAB opinions are organized or find a better way to summarize the issues.

- Other judges urged: (1) filing amicus briefs only when you have something to say beyond what the parties say; (2) restricting reply briefs to points raised in the opponent’s brief; and (3) often not using all of your allotted pages or minutes.

Six years for “deepfakes” – BRYAN GARNER has identified a significant word that emerged in each year since 2000. “Deepfakes” was born in 2018. It’s a blend word: deep as in “deep learning” + fakes. He defines it as, “a false video, audio recording, or other medium that is generated or manipulated by computer, often using AI, with the intent to deceive . . . .”

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

May 24, 2024

MAKE COURT BRIEFS AND OPINIONS SHORT . . . AND CLEAR

Readers TEIGE SHEEHAN and EDWARD CAJA recently recalled the Mark Twain quote, “I didn’t have time to write you a short letter so I’m writing you this long one.” The Curmudgeon agrees with that quote, but we should remember that clarity is paramount.

At the Federal Circuit Judicial Conference on May 14, where the judges got their say on writing and advocacy, the dominant theme was “keep it short.” Judges wanted shorter amicus briefs. Then, in LKQ v. GM this week, the Federal Circuit issued its first en banc patent opinion in 6 years.

The Curmudgeon believes IPO’s LKQ amicus brief was very clear and reasonably short on why the established framework for evaluating obviousness of patented designs should have been retained, but the court rejected that view. Bloggers are complaining that the court wasn’t clear enough on how to apply its test to designs in practice. Time will tell. Attend the IPO annual meeting in September, where you might have your say.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

May 17, 2024

“PATENTABLY INDISTINCT” OR “OBVIOUS VARIATION” IN DOUBLE PATENTING?

Patently indistinct is an arcane term in the patent rules. We’ve been hearing it a lot since the USPTO’s May 10 proposal to change the rule on using terminal disclaimers in what are now called “nonstatutory double patenting” cases.

When comparing claims in two or more commonly owned applications or patents, “patentably indistinct” means the same thing as “obvious variation.” Readers, please correct me if I’m wrong.

These terms don’t mean obvious in view of prior art, but obvious in view of another claim. For ease of understanding, “obvious variation (or variant)” seems to be the better term. We’ll leave the difference between variation and variant, if there is any, for another day.

In this column, we don’t say what the law is or should be. We just work on language. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

May 10, 2024

THERE IS A SECRET: MORE PAY FOR WRITING FEWER WORDS

More Money for Fewer Words? — A reader commented that, “My GW Law writing teacher said the highest paid attorneys in DC get paid for writing the shortest, succinct briefs and memos.” This goes against the claim that attorneys are paid by the word, but The Curmudgeon believes the reader’s teacher probably was correct.

Attorneys who are said to be highest paid often are known for studying a case relentlessly until they know absolutely everything about it, and then making only the strongest arguments. Also, 10th Circuit Judge Bob Bacharach suggests that the best-known attorneys at the appellate level have a knack for capturing the attention of judges in just a few lines of text.

Starting Sentences With “There Is”? – Writing guru Bryan Garner says it’s all right as long as the sentence is addressing the existence of something (as in the heading above). Otherwise, try to recast the sentence to avoid word clutter.

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

May 3, 2024

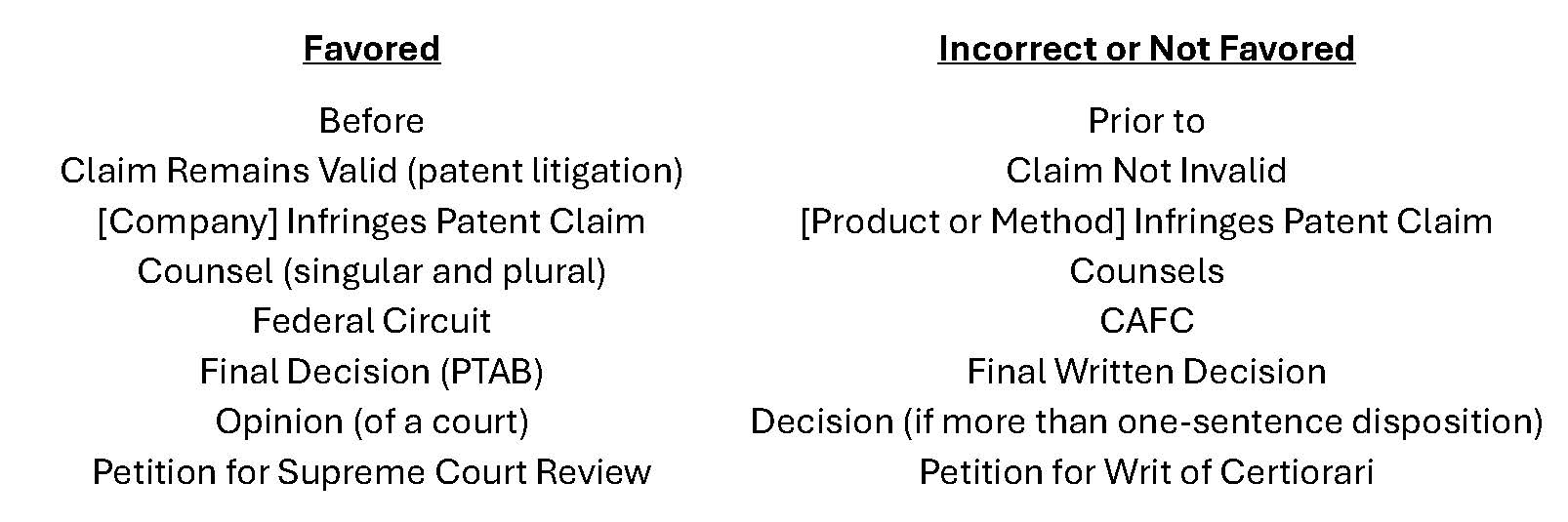

FAVORED BY THE CURMUDGEON IN IP DOCUMENTS

|

These terms have been discussed in past columns. Comments and questions are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your Friend,

The Curmudgeon

April 26, 2024

LIMITING USE OF ACRONYMS IN IP DOCUMENTS (CONT.)

Several people commented on last week’s column on PHOSITA. The statement that all IP acronyms except “IPO” should be stamped out was a joke, but acronyms do make reading difficult for those who aren’t fluent in IP-ese. (Strictly speaking, IPO and CAFC are “initialisms” because the letters are pronounced individually.)

Entrenched abbreviations are virtually impossible to eradicate. Chief Judge Markey’s goal of calling the court the Federal Circuit instead of the CAFC has never been fully realized. PHOSITA is entrenched too, and unnecessary whichever way you spell it. One person doesn’t like PHOSITA because he doesn’t know whether to pronounce it “FOSS-i-ta” or “foh-SEE-ta. He doesn’t like the Federal Circuit’s new alternative, POSA, because it makes him think of POSER.

Reader DAVID BLACK said, “[It’s] always reassuring to know we aren’t talking about paid time off, power take off, or a parent-teacher organization.” We shouldn’t adopt acronyms that have already been taken. Can we get Wall Street to stop using IPO for initial public offering?

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

April 19, 2024

WHAT DOES “A” MEAN IN A PATENT CLAIM? HOW DO WE SPELL PHOSITA?

Shifting sands? Writing on his blog, IPO member KEVIN NOONAN mused that “most verities in patent law are not eternal . . . .” He was referring to the supposed rule that “a” in a patent claim means “one or more.” An April 1 opinion by the Federal Circuit in Janssen v. Teva suggested that in a claim “a psychiatric patient” might have meant only one.

While reading Jannsen, The Curmudgeon stumbled on to another possible shift. The court used the acronym “POSA,” which the court said was for “person of ordinary skill in the art.” Used it 32 times. The common spelling is “PHOSITA,” for “person having ordinary skill in the art.” The “H” is for “having,” tracking the statute.

By coincidence, this week an anonymous reader asked, “whether word limits in briefs encourage the use of acronyms (e.g., PHOSITA) that only patent lawyers understand?” The Curmudgeon wants to stamp out all acronyms and initialisms . . . except IPO.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

April 12, 2024

READER COMMENTS AND CHURCHILL QUOTE

Last week’s patent issues were: allowing multiple-sentence claims; distinguishing between “eligibility” and “patentability”; using “indicators” instead of “indicia” for nonobviousness; and using “valid” instead of “not invalid” for claims.

Multiple-Sentence Claims – RAY DOSS said, “If we can make patents clearer and shorter, keeping appropriate protection, I am in! But I’m happy to make a bet . . . [that] when given multiple sentences, our colleagues find a way to write a novel!”

Eligibility v. Patentability – WALT LINDER uses the term “patent-eligible subject matter.” JEFF INGERMAN said that he used to use “patentable subject matter.” He likes “eligibility” better but thinks adding “subject matter” to “eligibility” doesn’t make it any clearer.

Indicators v. Indicia and Not invalid – People said good points but not keeping anyone awake at night.

Someone recalled this quote from Winston Churchill:

Short words are best and the old words when short are best of all.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

April 5, 2024

THE CURMUDGEON PONDERS PATENT TERMINOLOGY

- Claims are limited to one sentence, giving us some of the world’s longest sentences. Would multiple-sentence claims be clearer or shorter?

- The word “eligibility” isn’t in the statute, but people use it to explain section 101. Non-experts confuse “eligibility” with “patentability.” Is it clearer to say “subject matter eligibility”?

- Courts say “objective indicia of nonobviousness,” but “indicia” is only the plural. The singular is the little-known “indicium.” Cursed Latin. How about saying INDICATORS and INDICATOR so the singular would be obvious? No pun intended.

- Courts find patents “not invalid,” but the statute tells us patents are presumed valid. If we started saying “valid” when not proven invalid, would it stop “not invalid yet” jokes?

Send me your comments on these questions and anything else on your mind. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

March 29, 2024

LESSONS FROM COURT OPINIONS

U.S. Judge BOB BACHARACH says a key to clarity is to give readers CONTEXT before getting into detail. Judge STOLL of the Federal Circuit did it on March 25. She opened with:

This case concerns the seven-day trip of two transcatheter heart valve systems in and out of San Francisco to attend a medical conference. Once in San Francisco, however, the . . . systems did not attend the . . . conference. They sat in a bag . . . in a hotel closet . . .

In the same case, Judge LOURIE started with CONTEXT too: “I respectfully dissent because the majority perpetuates the failure of this court . . . to recognize the meaning of the word ‘solely’ . . . .”

Referring to my column about the March 7 Federal Circuit opinion that construed the claim term “matingly engaged,” a reader suggested that the real problem was with the specification. Probably true, but awkward adverbs anywhere can be unclear.

Send me your comments. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

March 22, 2024

FINDING CLEARER WORDS FOR PATENT CLAIMS

In a nonprecedential claim construction opinion on March 7, the Federal Circuit devoted 12 pages to the use of “matingly engaged” to describe how one member in a system to cool electronic devices was connected to another member. This was an example of how even short, non-technical words can cause trouble.

The patent owner asserted that “matingly engaged” meant “mechanically joined or fitted together to interlock.” The challenger argued it meant “joined or fitted together to make contact.” The PTAB came up with a meaning different from either of the parties. After all that, the Federal Circuit adopted its own construction: “mechanically joined or fitted together,” and remanded the case.

“Matingly” is an awkward adverb that was created by taking a known word and adding “ly.’ Strunk and White recommend against creating awkward adverbs. Their guidance: “Words that are not said orally are seldom the ones to put on paper.”

Comments are welcome. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

March 15, 2024

DON’T SAY “CLEARLY” OR OBVIOUSLY” IN IP BRIEFS

In briefs and memos, you’re trying to persuade the reader of the soundness of your position. It’s tempting to say “clearly” at the beginning of a sentence to prepare the reader for a conclusory statement, but it’s counterproductive. Adverbs such as “clearly” and “obviously” signal an attempt to compensate for a weak argument.

The late Federal Circuit Judge DANIEL FRIEDMAN wrote, “The claim that a particular statutory provision covers the case does not gain strength by stating that it ‘clearly,’ ‘plainly,’ or ‘patently’ does so.” This was also a pet peeve of BILL SCHUYLER, the first IPO president (1972 to 1981) and teacher of a pioneering law school class in which teams conducted semester-long patent trials.

Some can still recall Schuyler’s pithy lectures on winning a case. He believed understatement was the best test of a good argument and assertions should stand on their own.

Comments are welcome. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

March 8, 2024

PRONOUNCING PRO HAC VICE AND AMICUS

The USPTO is proposing to change its practice for recognizing counsel to appear in a particular PTAB case “pro hac vice.” And the U.S. Supreme Court, with many blockbuster constitutional law cases this year, may see record numbers of “amicus” briefs. How do we pronounce these Latin terms?

Pro hac vice, known primarily to judges and litigators, has at least four pronunciations. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, three ways are: proh hahk VEE-chay, proh hak VI-see, and proh hak VEES. Also, according to one obscure internet site, it can be pro hahk VICE, as in vice president. The Curmudgeon hears the first way most often.

For amicus (short for amicus curiae), a term widely known among nonlawyers as well as lawyers and often not italicized, do you say “uh-MEE-kuhs” or “AM-i-kuhs”? According to Bryan Garner, the first pronunciation is predominant, but the second is common enough that it’s not considered an error. Plain English devotees may use “friend of the court” if not writing a brief.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address. Click here for the Curmudgeon Archives.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

March 1, 2024

FONTS, COMMAS, AND ORDER OF WORDS

Microsoft’s New Default Font is Aptos — Microsoft has rolled out to a wider audience its new default font named “Aptos.” It replaces Calibri, which has been the default for 17 years. You can still use Calibri or another font as your default. Aptos and Calibri are sans serif fonts. As far as the Curmudgeon knows, most courts and major newspapers are sticking with serif fonts such as Times New Roman.

PTAB Struggles with Missing Commas and Order of Words – Readers with stamina might be interested in an unusual PTAB decision, Netflix v. DivX (Feb. 22), a case on remand from the Federal Circuit. The PTAB judges in the majority and a rare dissenter debated the meaning of one limitation in a claim for 20 pages. They consulted some of the Curmudgeon’s favorite sources: Strunk & White and Bryan Garner. Questions included whether the claim drafters could have inserted commas and whether they observed the drafting principle of keeping related words together.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

February 23, 2024

INSIGHTS INTO WRITING FROM THE MASTERS

Frank Bruni — In a December column in the New York Times, he opined that wrestling your thoughts into logical form and presenting them in writing can be the best test of those thoughts. He said, “WRITING IS THINKING, BUT IT’S THINKING SLOWED DOWN . . . to a point where dimensions and nuances otherwise invisible to you appear.” (Emphasis added.) Good writing, he said, “announces your seriousness, establishing you as someone capable of caring and discipline.”

Bryan Garner — In the ABA Journal last year, Garner, Editor-in-Chief of Black’s Law Dictionary, defined CLARITY as “the quality you achieve when you get your ideas across, however difficult they may be, so they reliably reappear in the reader’s mind.” Abstractness can lead to loss of clarity. Sometimes you need to add a few words. It may be better to write “three to five” than “several.” Garner believes clarity demands a knack (that can be learned) for knowing what to emphasize and what to omit.

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

February 16, 2024

COMMENTS ON “THE LODESTAR” AND “EXEMPLARY”

Recently I said the name for the common method of calculating attorney fee awards, “the lodestar,” is repulsive legalese. Legendary attorney JOHN PEGRAM defends it.

He points out that the lodestar is more complex than merely hours times rate. He’s correct that the lodestar is a reasonable number of hours times a reasonable rate. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, it also may include other factors. But I still don’t see why a court had to name it in 1973 by appropriating a centuries-old, standard English word of general usage. One reader says it’s “a fancy, $10 word” and he likes “plain talking.” Let’s call it hours times rate or the Pegram method.

Last week I wrote on patent law’s use of “exemplary” instead of “example.” Reader JEFF INGERMAN responded that if you look hard enough, you can find definitions of exemplary close to example, but he thinks the ambiguity nevertheless is a reason for avoiding “exemplary” as an alternative to “example.”

Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

February 9, 2024

READER WANTS TO ERADICATE THE WORD “EXEMPLARY”

A reader’s pet peeve is patent law’s frequent misuse of the word “exemplary” as an alternative to “example.” The reader asserts, “[exemplary] is . . . a dangerous term for a patent prosecutor to use, but somehow it took root in our profession years ago and refuses to die.”

Patent law seems to be out of step with usage of “exemplary” everywhere else, including at the Supreme Court. Outside the patent world, something is “exemplary,” an adjective, when it’s the best it can be and worth imitating. See, e.g., OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY (2016). “Example” means, well, an example. As recently as last month, the Federal Circuit referred to “several exemplary methods . . . .“ Could ALL of the methods have been the best?

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

February 2, 2024

“LODESTAR” IN ATTORNEY FEE SHIFTING OPINIONS IS REPULSIVE LEGALESE

A conspiracy could be afoot to add more words in legal writing. Attorney fees have been awarded to the prevailing party in several IP cases lately. This month the USPTO announced an award of more than $400,000 in a PTAB case.

“Lodestar” is an ordinary word with origins back to the 14th century. It means a principle that guides someone’s actions. The Supreme Court accepted the word, probably by accident, to be the name of the most common method of calculating fee awards. Under the “lodestar method,” you multiply an attorney hourly rate by the number of hours worked. The result often is called “the lodestar.”

To me it’s reminiscent of “mother lode” for veins of gold or silver ore. Judges create clutter by writing “lodestar” up to 40 times in a single opinion. We don’t need that name, or any name, for the calculation or for the sum of money. Just call it the “attorney rate multiplied by hours” method.

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

January 26, 2024

PLAIN ENGLISH IN U.S. COURTS?

Some unnecessarily specialized language of U.S. court litigation may be fading away. The Curmudgeon takes no credit.

For example, “bench trial,” a term familiar only to lawyers and judges, seems less common. People say “nonjury trial” or “judge trial.” One of my pet peeves is judges calling themselves “the court.” Some judges now speak in the first person. They say “I” will decide the patent claim construction issue. Nothing wrong with that. Also, Latin words and phrases are less common.

We still have work to do. The creation of the PTAB in 2011 has resulted in a whole new vocabulary that isn’t understood even by many patent lawyers. And who knows what AI will do to plain English?

It brings to mind that the late Justice Antonin Scalia told audiences he defended the use of Latin to supplement English. “After all,” he would say, “There’s one field of law where neither English nor Latin is spoken — intellectual property law.”

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

January 19, 2024

THE READERS COMMENT

Patent Claim Construction – A reader observed that last week while I was explaining “a” or “an” in a patent claim generally means “one or more,” the Federal Circuit was construing “single” to mean “single.” (Pacific Biosciences, Jan. 9). The court relied on the meaning of the word in context and the pesky “comprising” was not in play, so the general rule on “a” and “an” was not affected.

Never Too Much Proofreading – A reader spotted a misspelling by a leading IP blogger who is known to be a careful writer. The blogger typed, “The case peaked [piqued] my interest . . . .” Too much wine over the holidays? It’s easy to type a word that’s pronounced the same and has a different meaning. Proofread. If you can’t spell, of course, you’re in trouble. Prof. Lemley said last year that his law students were brilliant on IP law, but clueless about the difference between “rein” and “reign.” These are judges’ law clerks.

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

January 12, 2024

DID YOU KNOW? IN U.S. PATENT LAW, “A” OR “AN” CAN MEAN “ONE OR MORE”

Why do outsiders think patent law is arcane?

In patent law, the terms “a” or “an” in a claim generally mean “one or more,” unless the patent owner shows a clear intent to limit the terms to “one.” That’s the established rule as articulated by the Federal Circuit in the FS.com case (2023), among others. In FS.com, the claim called for a fiber optic module comprising “a” “front opening. . . .” FS.com tried to escape infringement by arguing it used multiple front openings. The court said no dice.

“Comprising” in patent claims has a specialized meaning. Black’s Law Dictionary defines “comprising” as “embracing to the exclusion of others” in normal English. Black’s definition, however, is for “normal idiomatic writing outside the intellectual property context.” We’re abnormal. To avoid being considered arcane, should we say “including” instead of “comprising”?

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Your friend,

The Curmudgeon

January 5, 2024

ON THE TERM “BIGLAW”

At the end of 2023, the media published lists of the biggest of almost everything. Since law firms are getting bigger, with many firms of more than 200 lawyers and a few with 2,000 or more, let’s consider the term “BigLaw.”

The Curmudgeon writes it with two capital letters and no space in the middle. That seems to be the trend. Some write “Big Law” (with a space) or “Biglaw” (with one capital letter). Those with the most rizz write “BIGLAW”; those with no rizz write “big law.” The battle over whether to require spaces between words in a name already has been won by advertising executives. If you include the word “firm” in your sentence, write “BigLaw firm,” not “BigLaw law firm,” which is redundant.

BigLaw is not for everyone, but I love BigLaw. IPO has about 50 BigLaw members. Nearly all, of course, practice in other fields in addition to IP. Do we need “SmallLaw” for smaller firms, which I also love?

Comments are invited. Click on “Curmudgeon” at the bottom of this column for my email address.

Happy New Year!

THECURMUDGEON

December 15, 2023

WORDS IP WRITERS SOMETIMES MISUSE

Here are a few words the Curmudgeon has seen misused in IP writing recently: